by Michael Liss

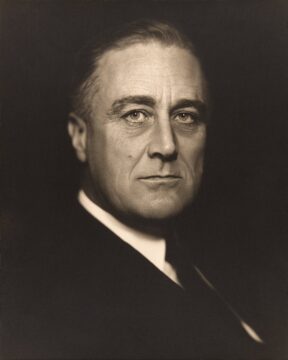

March 3, 1933. Herbert Hoover spent his final hours in the White House in anger and despair. Angry that he’d been decisively rejected by an electorate wrongheaded enough to not realize the wisdom of his policies—even when the evidence of their efficacy had been there for all to see. Despairing that his successor Franklin Delano Roosevelt was such a dilettante, an unworthy lightweight at a time when all serious men understood the necessity for prudence, for careful adherence to sound principles and practices.

He was also profoundly worried. “The Great Engineer” could see that the cracks in the foundation that he had so carefully begun to mend were giving way. Unemployment remained stubbornly high. Europe was deeply unstable and calling home from the U.S. its reserves of gold. Currency was increasingly scarce, and there was an acute loss of confidence in the domestic banking system—many banks could not meet the demand for cash. Without sufficient cash, the economy would completely seize up, and any scrip that might be issued in lieu of it would cause rampant inflation.

Hoover thought he knew the reason: His leadership was coming to an end. The clear policy statements he had made over the course of the previous year—indeed his efforts ever since the Crash itself—had painfully, but certainly, eased the economy back from the brink. Now, he believed all that good was being undone by the public’s anxiety that FDR would abandon his proven approach.

It’s not as if Hoover hadn’t warned the electorate: In his October 31, 1932 campaign speech in Madison Square Garden, he laid out the stakes: elect FDR and “[t]he grass will grow in streets of a hundred cities, a thousand towns; the weeds will overrun the fields of millions of farms if that protection be taken away. Their churches, their hospitals, and their schoolhouses will decay.” Read more »

Sughra Raza. Finding Color. Boston, January, 2026.

Sughra Raza. Finding Color. Boston, January, 2026.

Any sufficiently advanced technology might be indistinguishable from magic, as Arthur C. Clarke said, but even small advances–if well-placed–can seem miraculous. I remember the first time I took an Uber, after years of fumbling in the backs of yellow cabs with balled up bills and misplaced credit cards. The driver stopped at my destination. “What happens now?” I asked. His answer surprised and delighted me. “You get out,” he said.

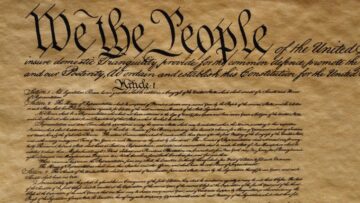

Any sufficiently advanced technology might be indistinguishable from magic, as Arthur C. Clarke said, but even small advances–if well-placed–can seem miraculous. I remember the first time I took an Uber, after years of fumbling in the backs of yellow cabs with balled up bills and misplaced credit cards. The driver stopped at my destination. “What happens now?” I asked. His answer surprised and delighted me. “You get out,” he said. Several years ago I was the moderator of a bar association debate between John Eastman, then dean of Chapman University School of Law, and a dean of another law school. The topic was the Constitution and religion. At one point Eastman argued that the promotion of religious teachings in public school classrooms was backed by the US Constitution. In doing so he appealed to the audience: didn’t they all have the Ten Commandments posted in their classrooms when growing up? Most looked puzzled or shook their heads. No one nodded or said yes. Eastman appeared to have failed to convince anyone of his novel take on the Constitution.

Several years ago I was the moderator of a bar association debate between John Eastman, then dean of Chapman University School of Law, and a dean of another law school. The topic was the Constitution and religion. At one point Eastman argued that the promotion of religious teachings in public school classrooms was backed by the US Constitution. In doing so he appealed to the audience: didn’t they all have the Ten Commandments posted in their classrooms when growing up? Most looked puzzled or shook their heads. No one nodded or said yes. Eastman appeared to have failed to convince anyone of his novel take on the Constitution.

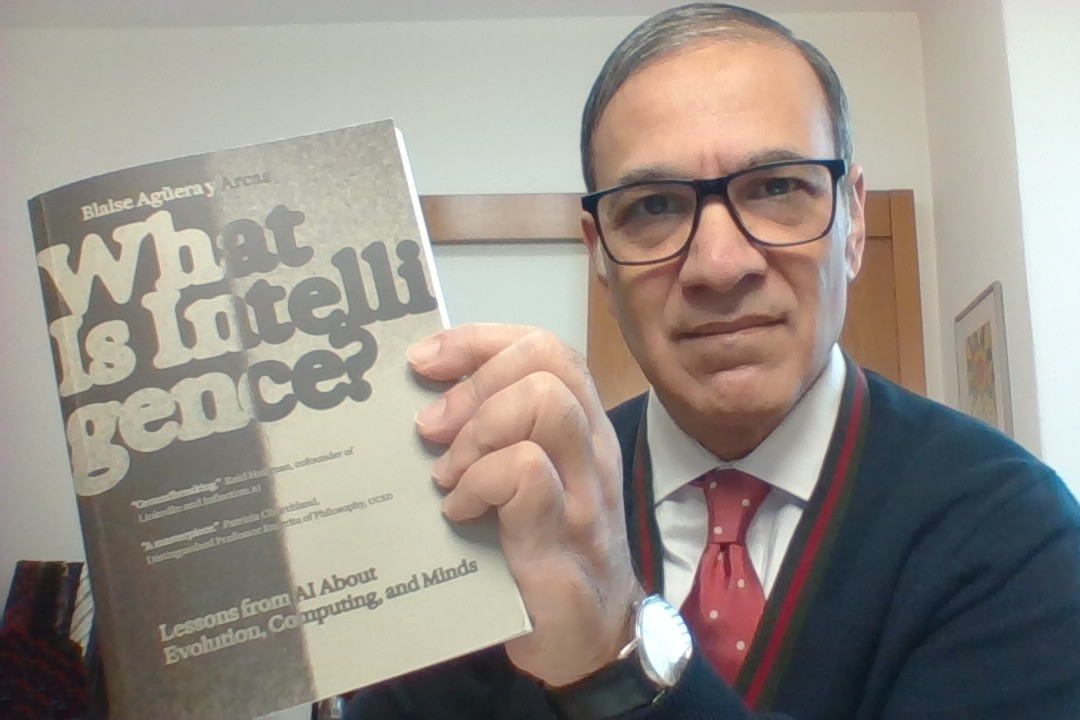

The question of whether AI is capable of having conscious experiences is not an abstract philosophical debate. It has real consequences and getting the wrong answer is dangerous. If AI is conscious then we will experience substantial pressure to confer human and individual rights on AI entities, especially if they report experiencing pain or suffering. If AI is not conscious and thus cannot experience pain and suffering, that pressure will be relieved at least up to a point.

The question of whether AI is capable of having conscious experiences is not an abstract philosophical debate. It has real consequences and getting the wrong answer is dangerous. If AI is conscious then we will experience substantial pressure to confer human and individual rights on AI entities, especially if they report experiencing pain or suffering. If AI is not conscious and thus cannot experience pain and suffering, that pressure will be relieved at least up to a point.

Jacob Lawrence. Migration Series (Panel 52).

Jacob Lawrence. Migration Series (Panel 52).